This month’s issue of Mondo Arc magazine features some of my work from Dev Diwali Festival in Varanasi. See the story here, or scroll down for the unedited question and answers. Most of these images are made during my annual photography tour to Varanasi, which we conduct in November.

This month’s issue of Mondo Arc magazine features some of my work from Dev Diwali Festival in Varanasi. See the story here, or scroll down for the unedited question and answers. Most of these images are made during my annual photography tour to Varanasi, which we conduct in November.

Q: Tell me about the experience of creating the images in Varanasi…how did you chose the subject.

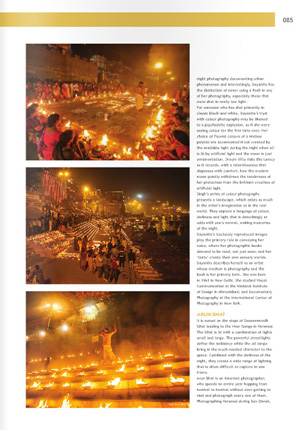

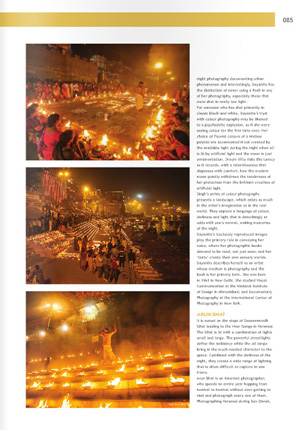

Varanasi has an unseen depth to it, rarely understood by its visitors. During the day, it’s a busy mix of pious pilgrims hoping to earn merit in the other world, businesses that depend on them and tourists who are looking to witness all this. As the night falls, the dimly lit alleys grow quiet and everyone congregates at an explosion of lights at Dasaswamedh Ghat, where the evening ritual of Ganga Aarti is performed by priest swaying torches under floodlit steps leading to the river.

Behind all this is a belief that moves the city and an energy that holds its constructs together. My motive has always been to capture this belief and energy that serves as the city’s foundation. I attempt go behind the faces and their interactions, trying to catch an unseen flow of otherworldly forces that appear define the city’s way of life. The people, the lights and the rituals form manifestations of this internal energy through which I try to represent the ethereal mystery of the city.

In the second half of June, I travelled with Pugdundee Safaries through the wilderness of Madhya Pradesh, seeing life in the jungles and witnessing some fairy-tale-like events unfold in front of my eyes.

It was dark when I arrived in Satpura. I couldn’t see much, but the absence of cellphone networks gave me hint of what I should expect. The next morning, we headed out when it was still dark, depriving me of the details of the place where I was staying. There were words spoken previous night–about a jamun tree, the river waters that surrounded us and the animals that roamed the region. They would have to wait for the afternoon until I came back from our sortie into the protected areas of Satpura National Park.

It was dark when I arrived in Satpura. I couldn’t see much, but the absence of cellphone networks gave me hint of what I should expect. The next morning, we headed out when it was still dark, depriving me of the details of the place where I was staying. There were words spoken previous night–about a jamun tree, the river waters that surrounded us and the animals that roamed the region. They would have to wait for the afternoon until I came back from our sortie into the protected areas of Satpura National Park.

The onset of monsoons and the eruption of life

Light seeped in from the sky as we waited at the office of the forest-department for our permits. A long ribbon of glint on earth revealed the backwaters of Tawa River that flowed between us and the park. Beyond, the land rose quickly to form the hills of Satpura Ranges, now covered in tender greenery that had erupted after the first rains of the season. The skies were decorated with patches of clouds and the ground was moist with the night’s precipitation. Monsoon had imprinted its signature, assertively declaring the end of summer and rekindling the fecundity of the forest.

How is it to live in a village at the base of a 20,000 feet high mountain forever covered in snow? How does one endure winter temperatures that can go down to -20C or lower? What is like to be in the company of yaks in summer and snow-leopards in winter? What does it take to survive in such a place for centuries, when modern facilities did not exist? I went to Langza to find answers.

Langza Village, with 6,300m high Chau Chau Kang Nilda Peak in the background.

Langza is no ordinary village. Located above 14,000 feet in Spiti Valley at the crossroads between Tibet and India, where the sun shines strongly over a brown treeless mountainscape in summers, where no rain falls during the monsoons and the winter’s snow can hide your footprints for four months, people have lived for a millennium with little interaction with the outside world. Before the modern world could connect with the people of Spiti, they lived an isolated, nearly self-subsistent life depending on their crop of barley for cereals and livestock for every other needs. They worked hard through the summer months, growing the year’s food and herding their sheep into the high-altitude meadows. The barren winters were for a slower pace of life, for festivities, celebrations and weddings, where barley chang flowed free from a yak-horn cup and the feet moved freely to the rhythm of drums. Only the strongest and the bravest travelled far and wide, to procure salt for the meal and timber for the houses. Everything else was made at home.

This month’s issue of Mondo Arc magazine features some of my work from Dev Diwali Festival in Varanasi. See the story here, or scroll down for the unedited question and answers. Most of these images are made during my annual photography tour to Varanasi, which we conduct in November.

This month’s issue of Mondo Arc magazine features some of my work from Dev Diwali Festival in Varanasi. See the story here, or scroll down for the unedited question and answers. Most of these images are made during my annual photography tour to Varanasi, which we conduct in November.